Rain lashed California’s Donner Summit. During the midwinter downpour, Andrew Schwartz, a Ph.D. atmospheric scientist and director of the Central Sierra Snow Lab, noticed runnels forming as water percolated through the site’s snowpack. He snapped a photo and posted it to Twitter.

At home in nearby Reno, Nevada, Anne Heggli perked up when she saw the post. A staff research scientist at the Desert Research Institute, Heggli was studying rain-on-snow events at the lab. She called Schwartz.

“I’m getting in my car,” she said. “Can I come dig a snowpit?”

An hour later, after excavating 51 inches of sodden snow, she found 3.5 inches of standing water atop the ground, a potential flood with nowhere to go but downhill. That soggy shoveling was a brief but evocative moment in Heggli’s groundbreaking push to develop a method for predicting rain-on-snow events. Her study is one example of what Schwartz hopes to facilitate at the lab: research that helps inform water managers, hydrologists, and weather forecasters, thus influencing the lives of residents who depend on western watersheds.

Mountain snowpacks can only hold so much water. During periods of sustained rain, they can become saturated. Compared to melting, when water generally seeps out slowly, the outflow from rain-on-snow events can cause intense flooding.

Using the lab’s historical records, Heggli examined 14 years of soil and snow saturation data to uncover a signature spike in hourly snow-water equivalent (SWE), which is the amount of water in the snowpack. The spike correlates with water moving over the ground during rain-on-snow events and gives water managers an early warning to anticipate flooding.

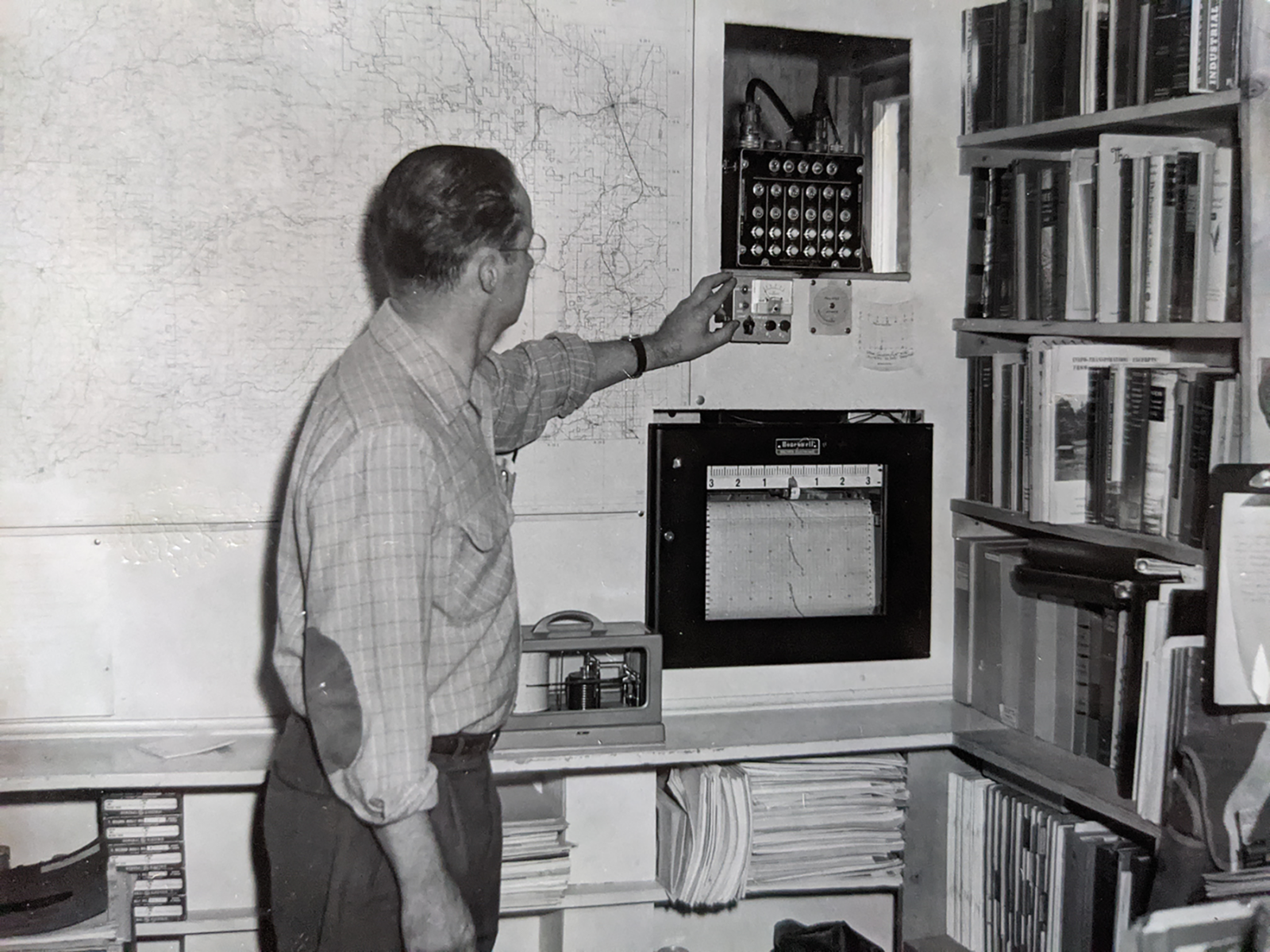

A scientist records measurements of outside conditions during the lab’s early days. Prior to the advent of digital instrumentation, scientists often recorded measurements by hand. Photo courtesy of Central Sierra Snow Lab.

Developing new methods like Heggli’s can be difficult. It often requires historical data, a place to house the research, and collaborators steeped in practical science. Northern California water managers and researchers say the snow lab is the perfect place for this work.

Built in 1946 on the Tahoe National Forest, it was one of three such facilities that the U.S. Weather Bureau and Army Corps of Engineers constructed around the West to monitor snowfall and predict spring runoff. The two-story building isn’t a lab in the forensically clean, white-coat sense. Rather, it’s a space for snow-science fieldwork and instrument development. Over time, the Montana and Oregon labs shuttered, but the Central Sierra facility maintained.

“Built in 1946 on the Tahoe National Forest, it was one of three such facilities the U.S. Weather Bureau and Army Corps of Engineers constructed around the West to monitor snowfall and predict spring runoff.”

It quickly developed a reputation for the practical research that still takes place there today. Lab founder Dr. Robert W. Gerdel, a Weather Bureau physicist, developed a nuclear snow gauge to measure SWE at the facility in 1948, paving the way for remote sensing and data transmission, according to a retrospective from the Donner Summit Historical Society.

Gerdel’s invention laid the groundwork for the more than 900 SNOTEL sites western water managers rely on today. Short for SNOw TELemetry and managed by the Natural Resource Conservation Service, these remote weather stations are located mostly on public land. Sensors at the sites measure snowpack, soil and climate conditions, available data that recreationalists and professionals use to understand the snowpack. The lab has a SNOTEL station, and devices used in the sites and other methods of weather and snow observation have been developed there.

“There’s a constant parade of new instruments that we’re testing, to see how well they [tell] us how much water is in the snowpack,” Schwartz said.

While SNOTEL stations offer huge datasets across watersheds, the lab offers a concurrent, yet different, resource—a staffed facility.

“As a testbed, it is enormously valuable, somewhere you can have new instrumentation or new ideas that you can test, and there’s [someone who] can actually get verification data that things are working or not working,” said Tim Bardsley, senior service hydrologist for the National Weather Service in Reno.

Andrew Schwartz makes measurements of snowpack depth, density, and water content using a Federal Sampler on January 26, 2022. These measurements are made multiple times a week at the lab to track the evolution of the snowpack during the season. Photo by Florence Low/California Department of Water Resources.

At the snow lab, professionals like Bardsley and researchers like Heggli can develop projects with Schwartz, knowing someone will be on site to collect manual measurements and confirm instrument accuracy. Over the decades, those arrangements have led to advancements in flood control and management of California’s precious water supply, according to the Historical Society.

For Heggli, who’s investigating a phenomenon that changes by the hour, having Schwartz there to give real-time updates is invaluable.

“You can’t put a dollar sign on that,” she said.

History hasn’t always been kind to the lab. The Forest Service oversaw it for decades but shuttered it in the late 1990s due to budget cuts, while maintaining ownership. In stepped the University of California-Berkeley, which has run it since. Fluctuations in funding have diminished staffing numbers, from several scientists in Gerdel’s time to one person for much of the post-millennium era.

“History hasn’t always been kind to the lab. The Forest Service oversaw it for decades but shuttered it in the late 1990s due to budget cuts, while maintaining ownership.”

This type of facility is rare. New Hampshire’s Mt. Washington Observatory, situated atop its namesake peak, provides researchers in the eastern U.S. a similar service, and Colorado’s Rocky Mountain Biological Lab looks much like the snow lab but focuses on ecological studies. Heggli and Bardsley could think of no analogous operationally focused hydrologic research labs in the West.

Perhaps the most crucial element of its success, and one Schwartz has championed since taking over in 2021, is an atmosphere of practical collaboration. Ecological and climate research is often largely theoretical, and researchers can be siloed in a university or government agency without a way to connect with professionals on the ground.

That’s where projects like Heggli’s fit in. She published a paper on her work in May 2022, and water managers in western Nevada are already implementing it. Bardsley uses it at the National Weather Service to understand the risk of flooding during rain-on-snow events and how to communicate that to downstream residents, water managers, and dam operators.

The snow lab is at the headwaters of the Yuba River, pictured here in January 2017, after the water rose by approximately 15 feet. One project hosted at the lab, Anne Heggli’s work studying rain-on-snow events, identified the start of runoff in the mountains nearly 24 hours prior to this peak. Heggli’s 2022 paper provides a decision-making framework that water managers and hydrologists now use to prepare for potential downstream flooding. Photo by JD Richey.

While researchers and managers expect the Sierra Nevada snowpack to shrink in coming decades, warming wintertime temperatures in the immediate future may lead to what Heggli’s paper calls “peak ROS,” or peak rain-on-snow. The Sierra will still have abundant snow, she writes, but warmer storms with more rain-on-snow events will lead to increased instances of potential flooding. That’s why a tool like hers, which she and Bardsley hope will one day incorporate quantitative predictive components, is so crucial.

By extension, that’s why the Central Sierra Snow Lab under Schwartz’s direction matters because scientists need a place to shut their computers and dig in the snow to ensure their research has real-world impact.

“All this stuff takes time,” Bardsley said. “Without people like Andrew who are engaged with both the research community and the operational community, it takes much longer.”

Submit your observations of the snowpack to the nonprofit Sierra Avalanche Center or Snow Pilot, an open-source, free software that allows users to graph, record, and database snowpit information, both of which provide crucial data to the snow lab. Spending time in other snowy ranges? Check out avalanche.org to find your local avalanche center.

About the Author

Tom Hallberg is the managing editor of Backcountry Magazine and a freelance writer based in Victor, Idaho. In addition to covering outdoor recreation, he enjoys any story about western communities finding solutions to difficult problems.

Cover photo: Instrumentation collects snowfall and snowpack data during a powerful winter storm at the UC Berkeley Central Sierra Snow Lab on December 27, 2021. The main lab building, in the background, is the location of both daily operations and employee living quarters. Photo courtesy Central Sierra Snow Lab.