In 1869, the completion of the first transcontinental railroad revolutionized American life. Railroads brought manufactured goods and settlers west, and gold and agricultural products east.

But before the railroad revolutionized American life, the Central Pacific Railroad and their workers had to pull off a remarkable feat of engineering – building a railroad through the heart of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. To navigate treacherous mountain passes, the railroad would need to be cut into the solid granite slopes by hand.

A view of the solid granite face of Donner Pass, where Chinese railroad workers dug 11 tunnels to complete the transcontinental railroad. Photo by the U.S. Forest Service

Clearing the granite was difficult and dangerous work, and by the mid 1860s Central Pacific needed more labors than they could find to help with the project. The company began to recruit workers fleeing poverty in southern China to fill the labor gap, and by the time the railroad was complete Chinese laborers made up over 90% of Central Pacific’s workforce.

The contributions and sacrifices of Chinese American railroad workers changed the course of American history. Today, you can still explore the heritage sites connected to the railroad in the Tahoe National Forest at Donner Pass.

Tahoe National Forest Heritage Sites

View of Summit Tunnels #6, #7, and #8 from above Summit Tunnel #6. Photo by the U.S. Forest Service

Summit Tunnel #6

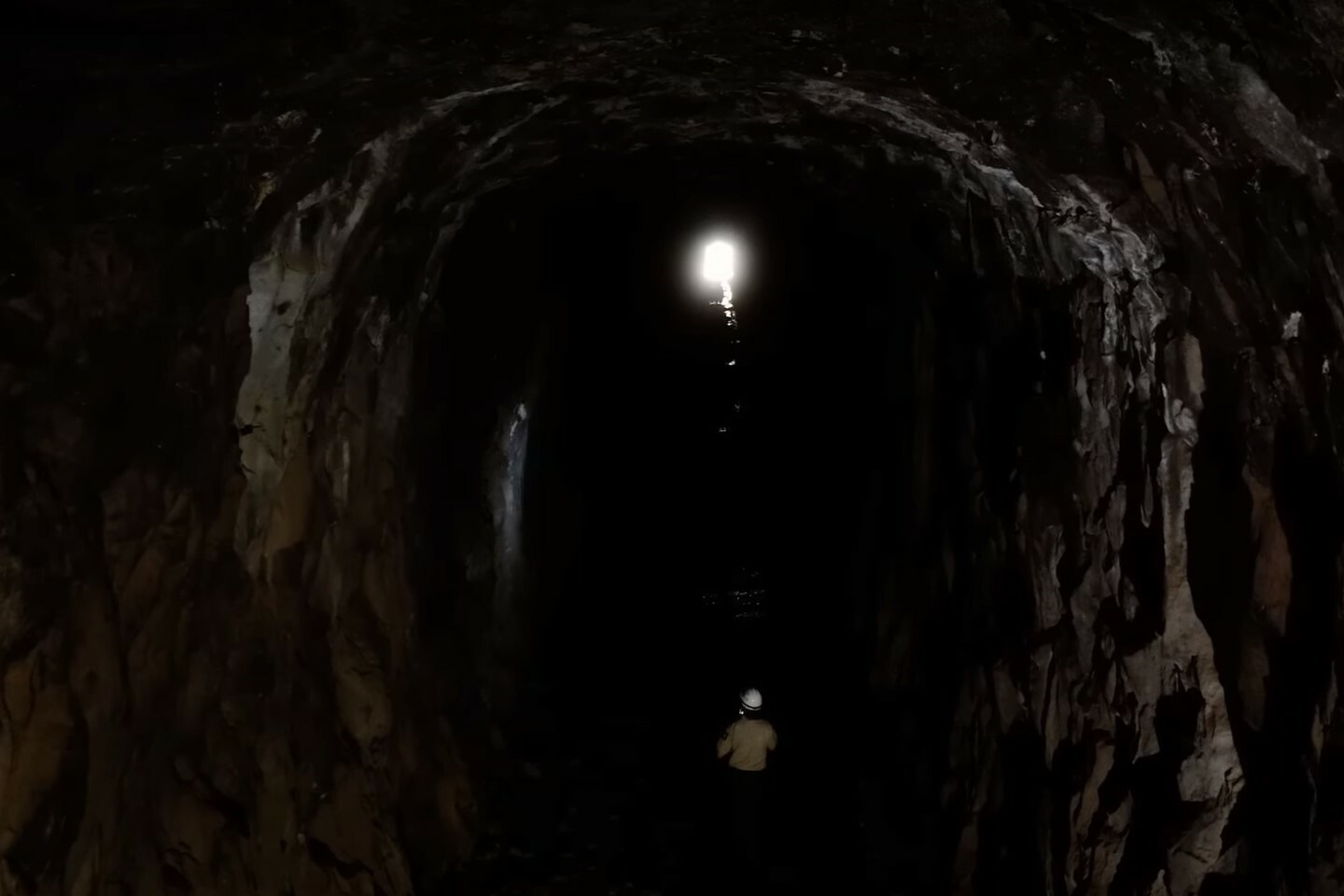

By the time it was completed in 1869, the transcontinental railroad ran through 11 tunnels dug out of solid granite in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Summit Tunnel #6 in the Tahoe National Forest is the longest of these tunnels at 1,687-feet - that is over five football fields long!

To construct the tunnel, Chinese labors used sledgehammers and chisels and create holes in the rock face where they could place and lite blasting powder. After the explosion, they moved the fallen rock out of the tunnel in carts. The work was difficult, dangerous, and excruciating slow – progressing only 14 inches a day.

Trains no longer run on the section of the historic transcontinental railroad that crosses Donner Pass, but the tunnels remain as a testament to the perseverance and courage and of the men that worked there.

U.S. Forest Service employee walks through Summit Tunnel #6. Photo by the U.S. Forest Service

Central Shaft

Because workers could only move 14 inches from each side of the tunnel per-day, Central Pacific decided to open a shaft at the top of the tunnel so that workers could also dig from the inside-out. It took workers three months to dig a 75-foot-deep shaft to the center of Summit Tunnel but once it was finished, the shaft doubled the construction speed of the tunnel.

Today, the top of the shaft is covered, but visitors can still imagine what it was like to descend into the mountain.

Donner Pass covered in snow. Photo by the U.S. Forest Service

Summit Camp

During the construction of the transcontinental railroad, Chinese laborers lived in camps along the railroad line that contained temporary store houses, blacksmith shops, stables, and rooms to eat and sleep.

Summit Camp, located just above the east entrance to Summit Tunnel #6, was one of the longest-standing work camps and housed men that worked on the tunnel from 1865 until 1869. Houses in the camp were built to withstand the snowy winters in Donner Pass, but workers still had to endure bitter cold and often traveled to-and-from the camp in tunnels dug out of snow.

While there are no buildings left at the site today, archaeologists have found historic objects Summit Camp’s residents left behind, including Chinese coins and porcelain rice bowls.

Lower China Wall. Photo by the U.S. Forest Service

China Wall

China Wall is a magnificent, 75-foot wall of rock that spans a ravine between two shorter railroad tunnels just east of Summit Tunnel #6. To build the wall, Chinese workers placed each stone by hand, gradually filling in the cracks with smaller stones until the wall was stable enough to support the railroad tracks.

The name “China Wall” commemorates the Chinese laborers’ monumental feat. The wall can still be seen today, more than 150 years after its construction.

Catfish Pond. Photo by the U.S. Forest Service

Catfish Pond

The catfish that call the clear, green waters at the top of Donner Pass home are an example of the railroad’s living history. Contained in the closed ecosystem of a pond, the first catfish in Donner Pass arrived with the first Chinese railroad workers in the late 1860’s. Chinese workers stocked nearby ponds to feed themselves. Their diet included dried fish, dried vegetables, and rice.

150 years later the descendants of these stocked fish can still be found in these waters - a living reminder of the workers that made the first transcontinental railroad possible.

A group on the Return to Gold Mountain Tour lead by the 1882 Foundation in partnership with the U.S. Forest Service, visiting the heritage sites of the Chinese railroad workers at Donner Pass. Photo by the U.S. Forest Service

A Self-Guided Heritage Tour of Chinese Railroad Worker Sites from Auburn to Donner Pass

For directions to each heritage site and more information about each location, check out the 1882 Foundation’s Self-Guided Heritage Tour of Chinese Railroad Worker Sites from Auburn to Donner Pass.

Source: Huang, Yuexian, editor. “Exploring the Path of Chinese Railroad Workers.” ExploreAPAHeritage.Com, 1882 Foundation, 2020.

Cover photo by the U.S. Forest Service.

--------

Every day, the NFF works to help make our forests – and the experiences people have on them – relevant to ALL Americans. We tell stories, highlight historical contributions of all peoples, explore forgotten legacies, and much more. This growing part of our mission requires unrestricted support from people like you. Will you join us today? It’s easy: just click here and offer your support. We thank you!