Walking through the forest, it’s easiest to pay attention to what is happening at eye level and above. Birds, sunlight, wind, branches, there’s a lot to observe. Next time you’re exploring a forest, consider what lies below the soil, leaves, and moss that carpet the ground. Underneath the forest floor, intertwined with the roots of the trees, is a fascinating microscopic network of fungus.

Woodwide Web

When most of us think of fungus, we imagine mushrooms sprouting out of the ground. Those mushrooms are in fact the “fruit” of the fungus, while the majority of the fungal organism lives in the soil interwoven with tree roots as a vast network of mycelium. Mycelium are incredibly tiny “threads” of the greater fungal organism that wrap around or bore into tree roots. Taken together, myecelium composes what’s called a “mycorrhizal network,” which connects individual plants together to transfer water, nitrogen, carbon and other minerals. German forester Peter Wohlleben dubbed this network the “woodwide web,” as it is through the mycelium that trees “communicate.”

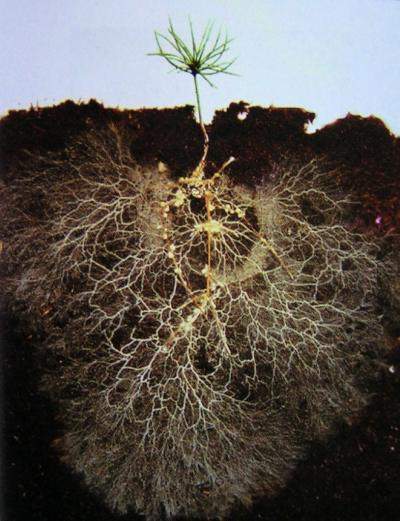

Photo by Dr. Shannon Guichon

Mushrooms are the fruit of the mycorrhizal network fungus, and connect trees through tiny threads called mycelium.

In healthy forests, each tree is connected to others via this network, enabling trees to share water and nutrients. For saplings growing in particularly shady areas, there is not enough sunlight reaching their leaves to perform adequate photosynthesis. For survival, the sapling relies on nutrients and sugar from older, taller trees sent through the mycorrhizal network. A study on Douglas-fir trees at England’s University of Reading, indicates that trees recognize the root tips of their relatives and favor them when sending carbon and nutrients through the fungal network.[1]

Ecologist Suzanne Simard hypothesizes that the fungus linking the trees is motivated by the need to secure its own source of carbon. The mycorrhizal network plays a distribution role to keep the mycelium-connected trees alive and healthy and the fungi’s supply of carbon consistent.[2] As a sort of payment for their services, the mycorrhizal network retains about 30% of the sugar that the connected trees generate through photosynthesis. The sugar fuels the fungi, which in turn collects phosphorus and other mineral nutrients into the mycelium, which are then transferred to and used by the trees.[1]

Mother Trees

A linchpin in the tree-fungi networks are hub trees. Also referred to as “mother trees,” these are the older, more seasoned trees in a forest. Typically, they have the most fungal connections. Their roots are established in deeper soil, and can reach deeper sources of water to pass on to younger saplings. Through the mycorrhizal network, these hub trees detect the ill health of their neighbors from distress signals, and send them needed nutrients.[1]

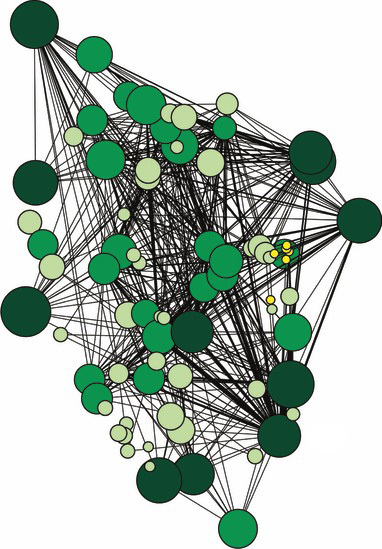

This diagram shows the connections between, where older and more connected trees are shown in dark green, while young trees just establishing themselves to the network are paler green. Source.

These findings suggest trees have developed complex symbiotic relationships for species survival. The mycorrhizal network is an integral part of this connectivity, and while the fungi are often acting in their own best interests, they facilitate health and survival of even the biggest trees.

Next time you’re visiting a forest, as you wander through the trees, take a moment to think about the complex exchanges happening underneath your feet. The mycorrhizal network is critical to supplying the life-giving nutrients that keep our forests healthy.

A cross-section of the a seedling connected to the mycorrhizal network. Source.

Next time you’re visiting a forest, as you wander through the trees, take a moment to think about the complex exchanges happening underneath your feet. The mycorrhizal network is critical to supplying the life-giving nutrients that keep our forests healthy.

Cover photo by Kirill Ignatyev

--------

Did you learn something new in this blog post? We hope so! The ecology that binds together everything on our National Forests is a fragile web, and we at the NFF are committed to doing all we can to ensure the healthiest forest ecology we can. To do so requires the support of caring individuals like you. Will you join us to ensure this critical work continues? Simply click here to join with thousands in this important work. Thank you!