The branches of an ancient oak sway in the moonlight. The whir of crickets and katydids fill the air with a chorus of chirps and trills. To the south, the mighty Ohio River roars - the dividing line between freedom and servitude.

For many African Americans fleeing slavery in the early 19th century, these waters were their first glimpse of free country on their long and dangerous flight north. To avoid detection, freedom seekers often traveled through farmland and forests under the cover of night – from one sympathetic community to the next.

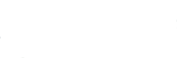

Historic map showing some of the routes along the Underground Railroad from 1830 to 1865. Many routes cross through what is now National Forest land in southern Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio, north of the Ohio River. Map courtesy of the U.S. Forest Service

After the Civil War, many of the rural communities that were stops along the Underground Railroad disappeared. But their stories live on in the forests that sheltered and concealed these paths to freedom. Look among the trees, and you will find the churches, cemeteries, and homesteads they left behind.

Abby Gill Miller and her daughters ca. 1910, all members of the Miller Grove community. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Forest Service

Miller Grove

Shawnee National Forest, Illinois

In the 1840s, a group of free and freed African Americans set out from Tennessee and settled in the Shawnee Foothills of southern Illinois. They named the free Black community they founded there, in present day Pope Country, Miller Grove.

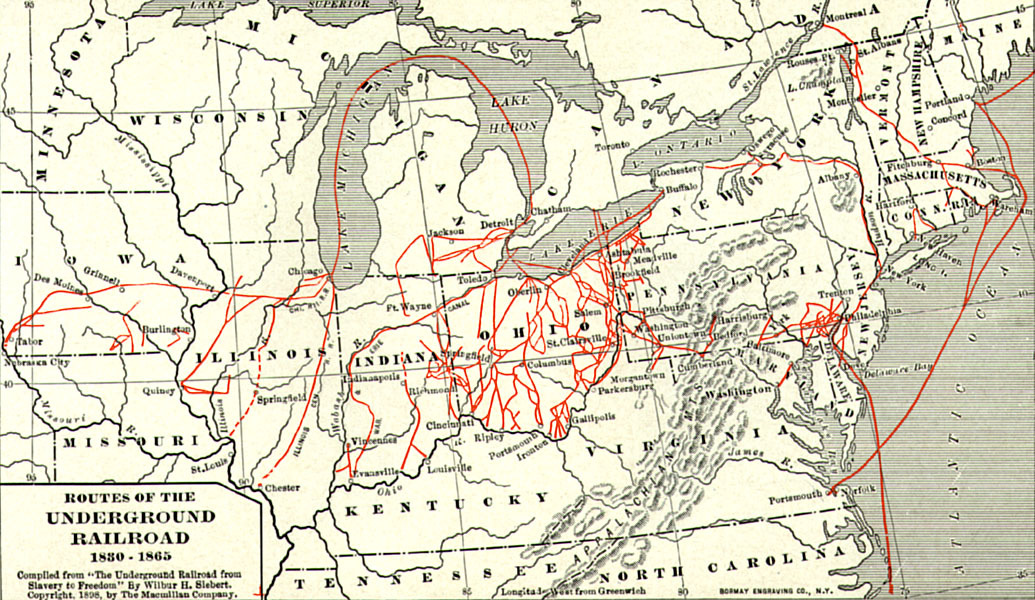

Crow Knob (left) and Sand Cave (right). Photos courtesy of the U.S. Forest Service

At the turn of the century, Miller Grove was home to more than 100 farmers and their families, had its own church that doubled as a school, and a cemetery. According to oral tradition, the residents of Miller Grove used the unique geography of the area to their advantage to help people evade capture and navigate to safety. Residents would lite bonfires atop Crow Knob, a sandstone bluff overlooking the community, to guide freedom seekers to safety in Sand Cave, a large sandstone rock shelter nearby.

Today, all that remains of Miller Grove is an archaeological site, but visitors can still visit Crow Knob and Sand Cave by hiking the River to River Trail near Eddyville.

Potts Creek on the Hoosier National Forest. Photo by Kathleen Ferguson

Lick Creek

Hoosier National Forest, Indiana

Lick Creek was settled in Orange County, Indiana, by eleven free Black families who fled North Carolina in the company of Quakers to escape increasingly restrictive laws on free Blacks in the South. Led by Jonathan Lindely, the first group of settlers arrived in 1811 – five years before Indiana became a state. Together, they formed an integrated community that certainly would have aided freedom seekers on their perilous journey north.

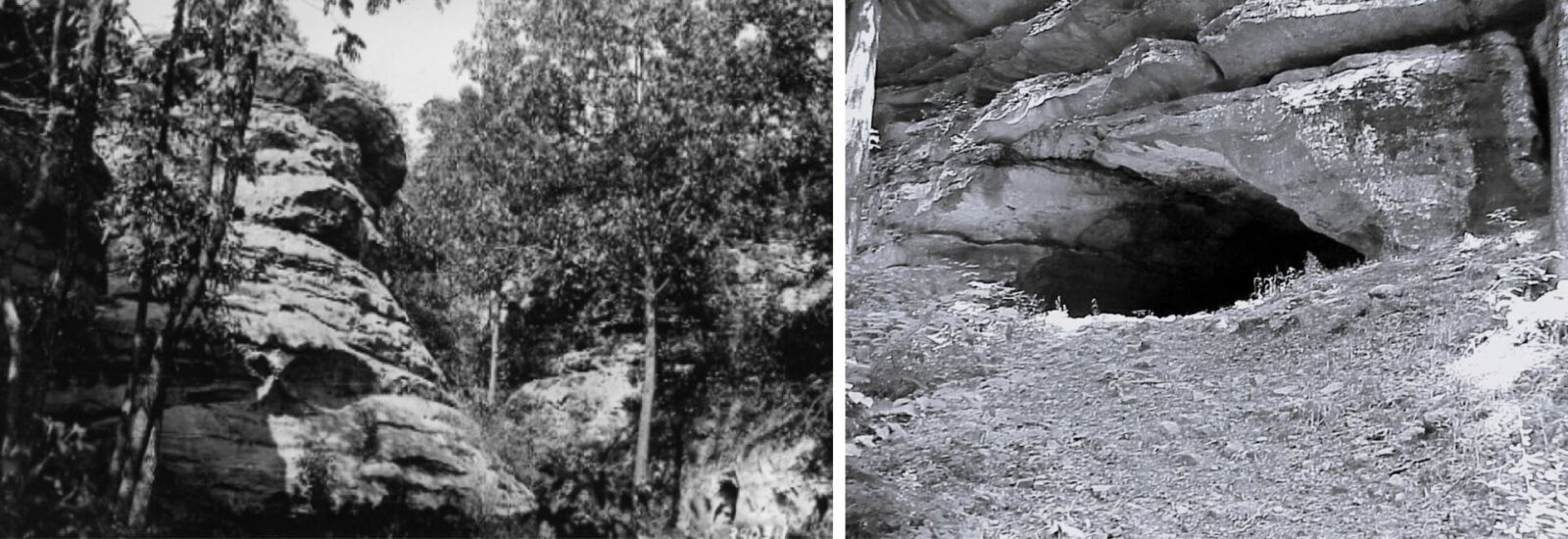

Farmer (left) and family cemetery (right) at Lick Creek. Photos courtesy of the U.S. Forest Service

The African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church was a focal point of community life and operated from 1843 to 1869. Volunteer efforts throughout the years have helped maintain the family cemetery near the site of the former AME church, where visitors can still find at least 14 marked headstones of the people that lived in Lick Creek. The last person to be buried there was Simon Locust in 1891 who served in the Civil War in Company E of the 13th Infantry Regiment of the U.S. Colored Troops.

To visit the cemetery, hike the 7-mile Lick Creek Trail through the scenic hardwood forests of southern Indiana and be on the lookout for the remnants of homesites from the settlement.

Paynes Cemetery. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Forest Service

Paynes Crossing

Wayne National Forest, Ohio

Paynes Crossing was founded as a farming settlement in the 1830s by free African Americans and freedom seekers fleeing Virginia. By that time, Ohio had become a hotbed of Underground Railroad activity, making Paynes Crossing one of many Black settlements in the state that assisted people escaping slavery.

Vesuvius Furnace. Photo by Kyle Brooks, courtesy of the U.S. Forest Service

Located deep in Ohio’s Hanging Rock Iron Region, the residents of Paynes Crossing were primarily farmers, coal miners, and iron workers. Iron was big business in southern Ohio and many of the wealthy industrialists who led iron production in the region, also known as ironmasters, were abolitionists. They used their company towns, ironworks, and transportation routes to secretly move freedom seekers through the area. The iron furnaces themselves served as stopping points, helping conductors and freedom seekers navigate northward.

Today, only the cemetery and a single farmstead remain as physical markers of the stories of Paynes Crossing. You can still visit one of the region’s many iron furnaces at the Lake Vesuvius Recreation Area.

Buffalo Beats Research Natural Area on the Wayne National Forest. Photo by Kyle Brooks, courtesy of the U.S. Forest Service

Want to Learn More?

You can discover more heritage sites on National Forests that bring our storied history to life on the U.S. Forest Service’s Sites of Civil Rights and Resistance Portal.

--------

Every day, the NFF works to help make our forests – and the experiences people have on them – relevant to ALL Americans. We tell stories, highlight historical contributions of all peoples, explore forgotten legacies, and much more. This growing part of our mission requires unrestricted support from people like you. Will you join us today? It’s easy: just click here and offer your support. We thank you!